The Mazarin Gallery

History of the Mazarin Gallery

Perfectly superimposed on the Mansart Gallery, located on the ground floor, the Mazarin Gallery has preserved most of the 17th century layout. The Gallery was designed by François Mansart between 1644 and 1646 at the request of Cardinal Mazarin, to host his rich collections of paintings and sculptures. The cardinal, on his return from Italy, entrusted the restoration to two Italian painters, Giovanni Francesco Romanelli and Gian Francesco Grimaldi.

The Mazarin Palace’s Long Gallery

In 1644, Mazarin commissioned François Mansart to build a new wing for his palace, made up of two superimposed galleries: a “lower gallery” intended for the Cardinal’s collections of ancient Greek sculptures, the future Mansart Gallery, and an “upper gallery”, designed to display the most beautiful pieces from the Cardinal’s collection of paintings, sculptures, and luxury furniture. The gallery had an antechamber at its northern end with a staircase directly leading to the garden.

Although Mansart originally designed a vault comprising three domes, Romanelli, an Italian painter commissioned by Mazarin to paint the upper gallery’s ceiling, had the vault converted into a continuous barrel vault. A plaster vault was therefore cast on a wooden lath secured on curved hoops, structurally linked to the frame.

This is how Henri Sauval described the gallery in his Histoire et recherches des antiquités de la ville de Paris (History and research into the Antiquities of the city of Paris) when he visited the Mazarin Palace in the 1650s:

“This gallery is illuminated on one side by eight large windows and decorated on the other by as many niches. The vault crowning it was frescoed in six months by Romanelli, a very handsome painter from Rome and one of the most diligent of the century. The niches are a little narrower than the windows opposite, but they rise from the parterre to the base of the vault, each one inhabited by a white marble ancient Greek statue of very particular excellence. The surrounding walls are covered in paintings, lined with cabinets, tables, busts with bronze and porphyry heads and veneered oriental alabaster shoulders, and brocade and gold cloth, hung with Crimson red damask, strewn with the Cardinal’s coat of arms and figures, and embellished with gold trimmings of extraordinary width and thickness from Milan.”

The Mazarin palace and its galleries were still so renowned after the cardinal’s death that Bernini was put up there during his stay in Paris in 1665.

From the Mazarin palace to the Bibliothèque nationale

On Mazarin’s death in 1661, the palace was divided between his two heirs. The Duke of Mazarin, who was married to the Cardinal’s niece Hortense Mancini, inherited the eastern part of the palace. As a staunch Catholic, the Duke loathed nudity, and, in 1670, ordered the vandalisation of the Cardinal’s ancient Greek collections, having the statues hammered with chisels. It was probably during this period that artists were hired to paint clothing on the naked bodies painted by Romanelli. This part of the palace, like the western part, was purchased from the heirs by John Law to be used as offices for the bank he created and the East India Company. After Law’s bankruptcy in July 1720, the Crown recovered the buildings and allocated part of them to the Royal Library.

The gallery, where the Department of Manuscripts was located from 1730, was not maintained. The structural fragilities of the ceiling and the damaged roofing led to numerous infiltrations. The very fragile damask wall hangings disappeared. In 1780, the roofs were in such a state of disrepair that the roofers refused to go up on them. The truss was removed and reassembled by the Bâtiments du Roi in 1782, and part of the ceiling was repaired in 1788.

By 1828, the gallery was in deplorable condition. Léon Laborde, archaeologist and politician, wrote:

“I urge all those who can to go and admire this great painting, to protest, through their praise, against the dilapidation in which it has been left and against the destruction with which it is threatened. Let their admiration not be dimmed by the cracks in the fresco, or by the racks of black manuscripts which hide Grimaldi’s paintings, or by the dust tarnishing the gilding. In a few weeks, with what it has cost over twenty years to draw up destruction estimates, we will rejuvenate all these magnificences.”

Labrouste’ restoration and Pascal’s conversion

Various restoration projects for the gallery were proposed by Visconti, the architect in charge of the library at that time, but these projects never came to anything. The Historical Monuments Commission commissioned surveys of the palace’s painted decorations in 1853 from the artist Jules Frappaz. While the surveys of most of the rooms faithfully documented the poor condition of the ceilings, for the Mazarin vault, Frappaz produced an idealised vision of the decorations, without recording any damage.

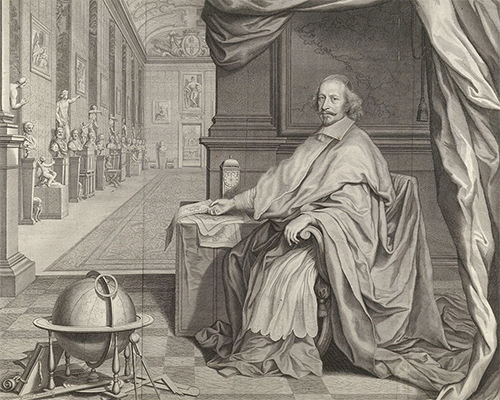

The first real restoration campaign was undertaken by Henri Labrouste between 1868 and 1872. He replaced the original wooden frame with a much more stable metal frame and restored all of the painted decorations on the gallery’s vault and walls. He replaced the 17th century damask with a marouflaged canvas featuring the Cardinal’s coat of arms inspired by the decoration portrayed in the Nanteuil engraving.

In 1878, when a new Manuscript reading room was being built, Jean-Louis Pascal converted the gallery into an exhibition space where the Bibliothèque’s treasures were displayed during the Universal Exhibition. However, the gallery’s structural fragilities resulted in various damage: infiltrations were noted on the garden side in 1924, and several librarians reported the fragility of the floor.

New conversion in 1927

The Mazarin Gallery was converted once again in 1927 under the direction of Alfred Recoura, the library’s architect. He enlarged the entrance door, covered the vestibule in grey canvas and blue strips, cleaned up the gallery’s decorations, carried out a series of partial restorations, completed the plumbing, installed 17th century Italian style chandeliers, fitted a ceiling light in the entrance hall, and installed electric lighting. The wall display cases installed by Pascal were removed and new display cases were placed in the centre. Parts of the murals on the bay window reveals, which had deteriorated again, were restored.

A new mural was painted in tempera in a dark green tone copied from an old Venetian damask, with ornaments executed with a tone-on-tone stencil. It was applied directly on the marouflaged canvases hung by H. Labrouste. Some of the work was carried out thanks to a donation from Florence Blumenthal.

Restoration in the 1970s

In 1955, major cracking was noted on the vaults and the window lintels, indicating structural movements. André Chatelin, the library’s architect at that time, requested monitoring and, in 1957, inventoried the gallery’s condition. He recommended conservation and repair work on interior fittings and the parquet floors.

When the wing built by Mansart was raised in 1972, Chatelin carried out a new modification of the roof truss and began renovating the gallery: the lighting was modernised in 1974 and the vault was reinforced and restored between 1975 and 1978. Romanelli’s painted decorations were restored by Genovesio-Lemercier. In 1978, the woodwork was restored, and the existing hanging was replaced with a crimson hanging in the Louis XIV damask style.

At the end of this work, the gallery became a temporary exhibition space. Between 2010 and 2016, as part of the renovation work on the entire site, the gallery was converted into a temporary reading room for the departments of Performing Arts and Manuscripts.

Mazarin Gallery decor

The Mazarin Gallery is 45.55 meters long, 8.20 meters wide and 9.20 meters high. With a surface area of 280 m², the 17th century vault has survived the tests of time. Decorated with golden stucco compartments by Ottaviano Ottoviani, it was frescoed in 1646-1647 in the purest Baroque style by Giovanni Francesco Romanelli and his studio, notably Paolo Gismondi for the grisailles. The ceiling’s iconography was inspired by Greco-Roman mythology, in particular Ovid’s Metamorphoses and from mythological and heroic subjects, such as Jupiter striking down the Giants – placed in the centre of the ceiling – Apollo and Daphne, the Judgement of Paris, and the Abduction of Helen and the Fire of Troy.

Twenty-two small scenes complete these large compartments. The window embrasures surmounted by a golden shell in bas-relief are painted as a fresco by the Italian artist Grimaldi Bolognese. It represents landscapes with trees in the foreground and a trompe l’œil balustrade.

The restoration of one of the jewels of the Richelieu site

A major feature of this essential part of the new Museum, the ceiling and its exceptional painted decorations have been completely restored by the teams of Alix Laveau and the Mariotti workshop. This large-scale project, which involved 22 restorers, allowed the frescoes to regain the freshness, transparency and lightness of their original colours. The murals and marouflaged canvases have also been renovated.

The modesty veils

The great discovery of this restoration project was the addition, shortly after Romanelli painted the vault in 1646-1647, of around fifty veils of modesty dotted about on the vault’s frescoes. These veils were most probably painted on in the 1660s, when the Duke of Mazarin, husband of the heiress of this part of the palace and a devout Catholic, had the nude sculptures vandalised. Jules Frappaz’s drawings, prior to Labrouste’s work in 1853, still showed these dressed bodies. Labrouste attempted to restore the original nudes by removing the veils, but only partially succeeded, forcing him to repaint over them in flesh colour. The bodies were “dressed” again and touched up during the restoration in the 1970s. The 2018 project was an opportunity to establish with certainty the work on these veils of which only four were original. It was therefore decided to conserve them and remove all the others, returning the vault to its original design as much as possible.

The restoration in images

An exceptional setting for exceptional works

The restored Mazarin Gallery has been returned to its original function as an exhibition space. It is now the setting for the new Museum, a veritable “Gallery of treasures” drawn from the encyclopaedic collections of the BnF: rare pieces, famous works or works from prestigious origins.

Pieces of the treasury of Saint-Denis: art objects, cameos, jewels and ivories, Throne of Dagobert and Charlemagne’s Chessboard are exhibited in the vestibule of the Gallery, etc. In the Gallery itself, collections from the Middle Ages to the present day are presented. A significant proportion of the collections is shown there in rotation.

Practical information

Opening times

Tuesday (late-night opening): 10 a.m. – 8 p.m.

Wednesday to Sunday: 10 a.m. – 6 p.m.

Closed on Mondays and select bank holidays*

The Museum is open on 8 May, Ascension Thursday, and 1 and 11 November.

* The Museum is closed on 1 January, Easter Monday, 1 May, Whit Monday, 14 July, 15 August and 25 December

Please note: due to the fragility of certain artworks, some pieces on display in the Mazarin Gallery and Rotunda are rotated every four months, showcasing the breadth of the BnF’s collections. These spaces are closed to the public while the pieces are rotated.

Mazarin Gallery closing dates: From Monday 2 to Friday 31 May 2024 inclusive

Rotunda closing dates: From Monday 2 to Friday 6 october 2023 inclusive

Access

Site Richelieu

5, rue Vivienne

75002 PARIS

Group activities

Reservation obligatory at visites@bnf.fr or on 01 53 79 49 49 (from Monday to Saturday, 9 am to 5 pm)

Rates

During the Mazarin Gallery’s closure period (from Monday 8 to Friday 19 January 2024 inclusive – every 4 months), Museum admission rates are lowered to 7 € (full rate), 5 € (reduced rate), 10 € (full rate coupled with an exhibition) and 7 € (reduced rate coupled with an exhibition).

Guided tours of the BnF’s Museum – Reservation